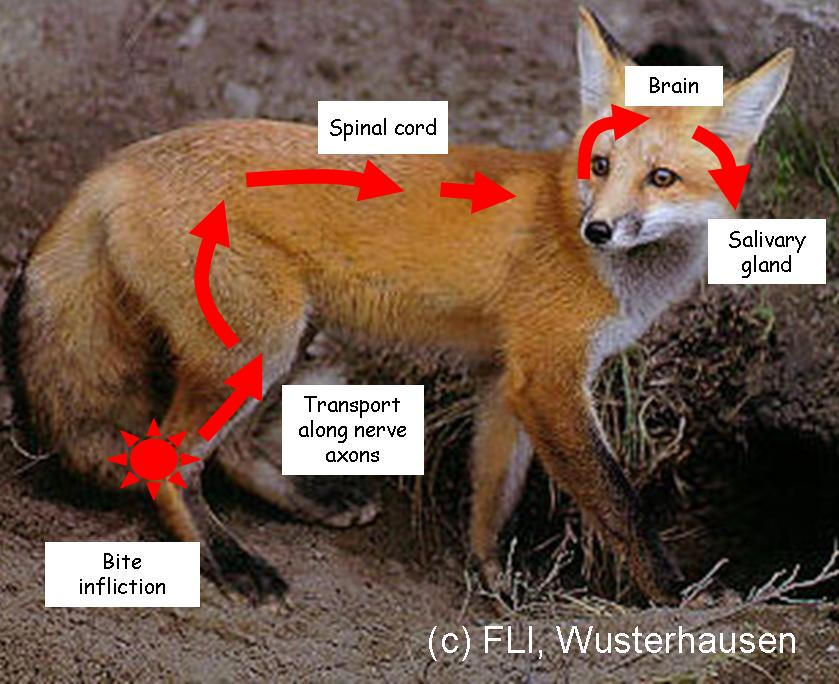

Transmission and pathogenesis

In most cases the disease is transmitted via the bite of

rabid animals which shed infectious virus with their saliva. The virus enters

the body through transdermal inoculation (i.e. wounds) or direct contact

of infectious material (i.e. saliva, cerebrospinal liquid, nerve tissue)

to mucous membranes or skin lesions. The virus cannot penetrate intact

skin.

In most cases the disease is transmitted via the bite of

rabid animals which shed infectious virus with their saliva. The virus enters

the body through transdermal inoculation (i.e. wounds) or direct contact

of infectious material (i.e. saliva, cerebrospinal liquid, nerve tissue)

to mucous membranes or skin lesions. The virus cannot penetrate intact

skin.

After entry the virus binds to cell receptors. Viruses

may replicate within striated muscle cells ore directly infect nerve

cells.

The virus then travels via retrograde axoplasmatic

transport mechanisms to the central nervous system. Both motor and

sensory fibres may be involved depending on the animal infected. The

incubation period varies from 2 weeks to 6 years (average 2–3 months)

depending on the amount of virus in the saliva, the site of inoculation

and the virus strain.

Once it has reached the CNS, rapid virus replication

takes place, causing pathologic effects on nerve cell physiology. The

virus then moves from the CNS via anterograde axoplasmic flow within

peripheral nerves, leading to infection of some of the adjacent

non-nervous tissues, for example, secretory tissues of salivary glands.

The virus is widely disseminated throughout the body at the time of

clinical onset. With shedding of infectious virus in saliva the

infection cycle of rabies is completed.